Free, Fair and Alive was published in September 3rd 2019 by New Society Publishers.

Click on the index below to read and sign up to our newsletter to receive notifications of new chapters.

Free, Fair and Alive was published in September 3rd 2019 by New Society Publishers.

Click on the index below to read and sign up to our newsletter to receive notifications of new chapters.

This book is dedicated to overcoming an epidemic of fear with a surge of reality-based hope. As long as we allow ourselves to be imprisoned by our fears, we will never find the solutions we need to help us build a new world. Of course, we have plenty of good reasons to be fearful — the loss of our jobs, authoritarian rule, corporate abuses, racial and ethnic hatred. Looming above all else is the warming of the Earth’s climate, an existential threat to civilization itself. We watch with amazement as space probes detect water on Mars while authorities struggle to find drinking water for people on Earth. Technologies may soon let people edit the genes of their unborn children like text on a computer, yet the means for taking care for the sick, old, and homeless remain elusive.

Fear and despair are fueled by our sense of powerlessness, the sense that we as individuals cannot possibly alter the current trajectories of history. But our powerlessness has a lot to do with how we conceive of our plight — as individuals, alone and separate. Fear, and our understandable search for individual safety, are crippling our search for collective, systemic solutions — the only solutions that will truly work. We need to reframe our dilemma as What can we do together? How can we do this outside of conventional institutions that are failing us?

The good news is that countless seeds of collective transformation are already sprouting. Green shoots of hope can be seen in the agroecology farms of Cuba and community forests of India, in community Wi-Fi systems in Catalonia and neighborhood nursing teams in the Netherlands. They are emerging in dozens of alternative local currencies, new types of web platforms for cooperation, and campaigns to reclaim cities for ordinary people. The beauty of such initiatives is that they meet needs in direct, empowering ways. People are stepping up to invent new systems that function outside of the capitalist mindset, for mutual benefit, with respect for the Earth, and with a commitment to the long term.

In 2009, a frustrated group of friends in Helsinki were watching another international climate change summit fail. They wondered what they could do themselves to change the economy. The result, after much planning, was a neighborhood “credit exchange” in which participants agree to exchange services with each other, from language translations and swimming lessons to gardening and editing. Give an hour of your expertise to a neighbor; get an hour of someone else’s talents. The Helsinki Timebank, as it was later called, has grown into a robust parallel economy of more than 3,000 members. With exchanges of tens of thousands of hours of services, it has become a socially convivial alternative to the market economy, and part of a large international network of timebanks.

In Bologna, Italy, an elderly woman wanted a simple bench in the neighborhood’s favorite gathering spot. When residents asked the city government if they could install a bench themselves, a perplexed city bureaucracy replied that there were no procedures for doing so. This triggered a long journey to create a formal system for coordinating citizen collaborations with the Bologna government. The city eventually created the Bologna Regulation for the Care and Regeneration of Urban Commons to organize hundreds of citizen/government “pacts of collaboration” — to rehabilitate abandoned buildings, manage kindergartens, take care of urban green spaces. The effort has since spurred a Co-City movement in Italy that orchestrates similar collaborations in dozens of cities.

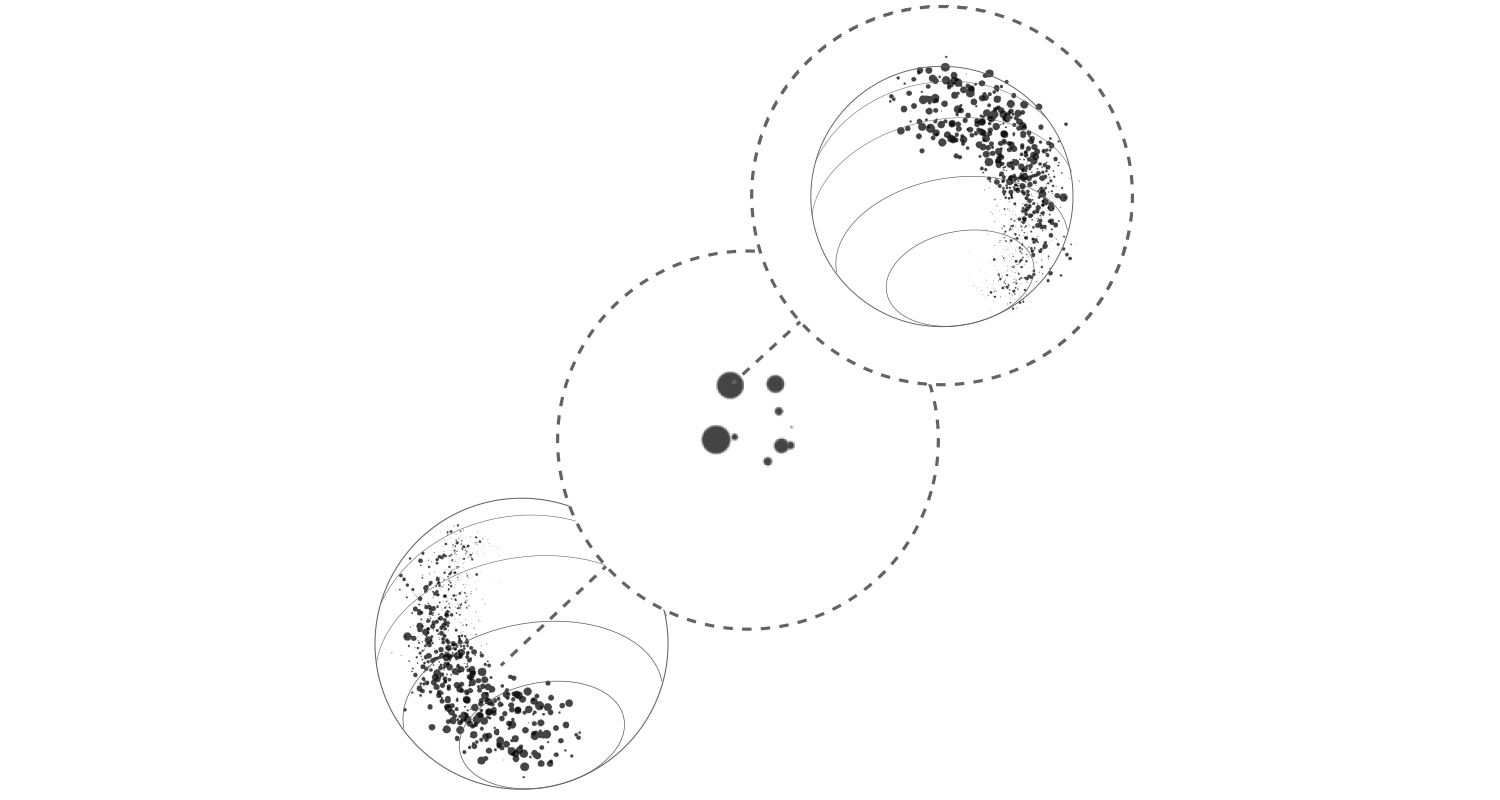

But in the face of climate change and economic inequality, aren’t these efforts painfully small and local? This belief is the mistake traditionalists make. They are so focused on the institutions of power that have failed us, and so fixated on the global canvas, that they fail to recognize that real forces for transformational change originate in small places, with small groups of people, beneath the gaze of power. Skeptics of “the small” would scoff at farmers sowing grains of rice, corn, and beans: “You’re going to feed humanity with… seeds?!” Small gambits with adaptive capacities are in fact powerful vehicles for system change. Right now, a huge universe of bottom-up social initiatives — familiar and novel, in all realms of life, in industrialized and rural settings — are successfully addressing needs that the market economy and state power are unable to meet. Most of these initiatives remain unseen or unidentified with a larger pattern. In the public mind they are patronized, ignored, or seen as aberrational and marginal. After all, they exist outside the prevailing systems of power — the state, capital, markets. Conventional minds always rely on proven things and have no courage for experiments even though the supposedly winning formulas of economic growth, market fundamentalism, and national bureaucracies have become blatantly dysfunctional. The question is not whether an idea or initiative is big or small, but whether its premises contain the germ of change for the whole.

To prevent any misunderstanding: the commons is not just about small-scale projects for improving everyday life. It is a germinal vision for reimagining our future together and reinventing social organization, economics, infrastructure, politics, and state power itself. The commons is a social form that enables people to enjoy freedom without repressing others, enact fairness without bureaucratic control, foster togetherness without compulsion, and assert sovereignty without nationalism. Columnist George Monbiot has summed up the virtues of the commons nicely: “A commons… gives community life a clear focus. It depends on democracy in its truest form. It destroys inequality. It provides an incentive to protect the living world. It creates, in sum, a politics of belonging.”1

This is reflected in our title, which describes the foundation, structure, and vision of the commons: Free, Fair and Alive. Any emancipation from the existing system must honor freedom in the widest human sense, not just libertarian economic freedom of the isolated individual. It must put fairness, mutually agreed upon, at the center of any system of provisioning and governance. And it must recognize our existence as living beings on an Earth that is itself alive. Transformation cannot occur without actualizing all of these goals simultaneously. This is the agenda of the commons — to combine the grand priorities of our political culture that are regularly played off against each other — freedom, fairness, and life itself.

Far more than a messaging strategy, the commons is an insurgent worldview. That is precisely why it represents a new form of power. When people come together to pursue shared ends and constitute themselves as a commons, a new surge of coherent social power is created. When enough of these pockets of bottom-up energy converge, a new political power manifests. And because commoners are committed to a broad set of philosophically integrated values, their power is less vulnerable to co-optation. The market/state has developed a rich repertoire of divide-and-conquer strategies for neutralizing social movements seeking change. It partially satisfies one set of demands, for example, but only by imposing new costs on someone else. Yes to greater racial and gender equality in law, but only within the grossly inequitable system of capitalism and weak enforcement. Or, yes to greater environmental protection, but only by charging higher prices or by ransacking the Global South for its natural resources. Or, yes to greater healthcare and family-friendly work policies, but only under rigid schemes that preserve corporate profits. Freedom is played against fairness, or vice-versa, and each in turn is played off against the needs of Mother Earth. And so the citadel of capitalism again and again thwarts demands for system change.

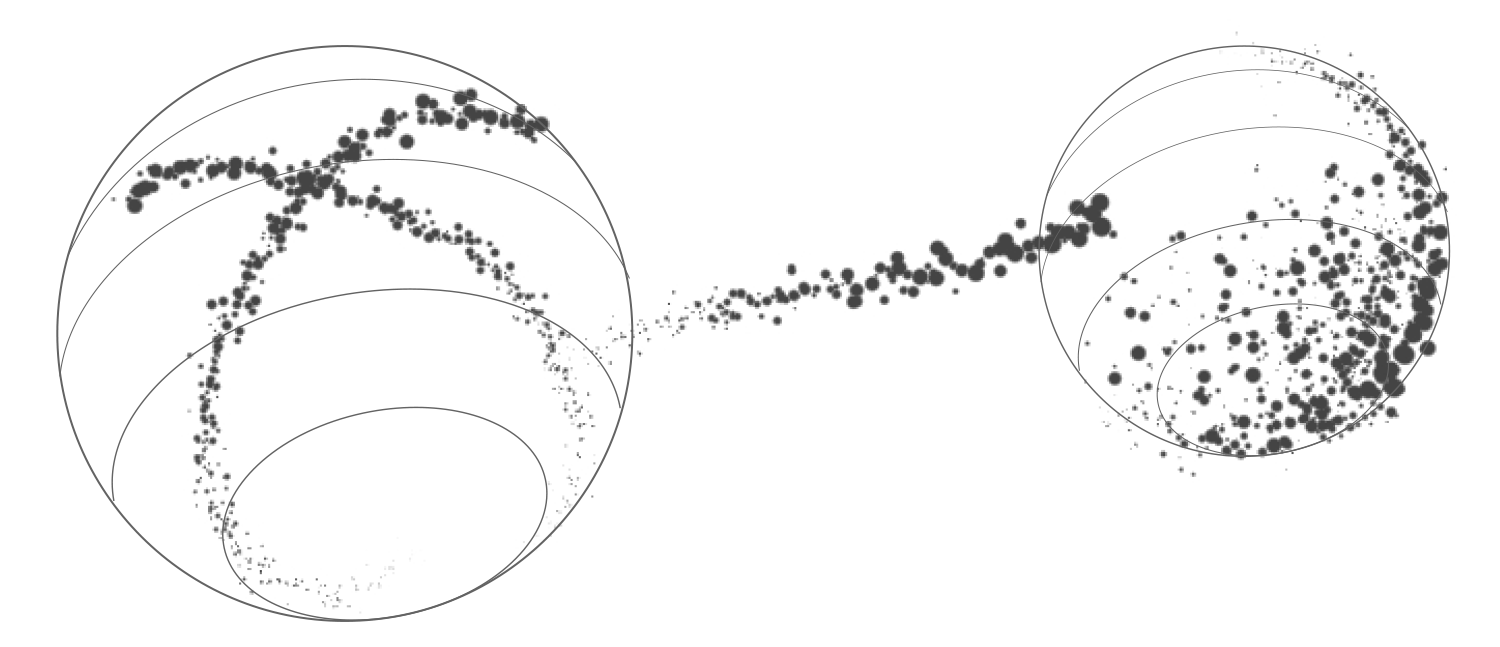

The great ambition of the commons is to break this endless story of co-optation and beggar-thy-neighbor manipulation. Its aim is to develop an independent, parallel social economy, outside of the market/state system, that enacts a different logic and ethos. The Commonsverse does not pursue freedom, fairness, and eco-friendly provisioning as separate goals requiring tradeoffs among them. The commons seeks to integrate and unify these goals as coeval priorities. They constitute an indivisible agenda. Moreover, this agenda is not merely aspirational; it lies at the heart of commoning as an insurgent social practice.

Not surprisingly, the vision of the commons we set forth here is quite different from that image presented (and derided) by modern economics and the political right. For them, commons are unowned resources that are free for the taking and therefore a failed management regime — an idea popularized by Garrett Hardin’s famous essay on the “Tragedy of the Commons.” (More about this later.) We disagree. The commons is a robust class of self-organized social practices for meeting needs in fair, inclusive ways. It is a life-form. It is a framing that describes a different way of being in the world and different ways of knowing and acting.

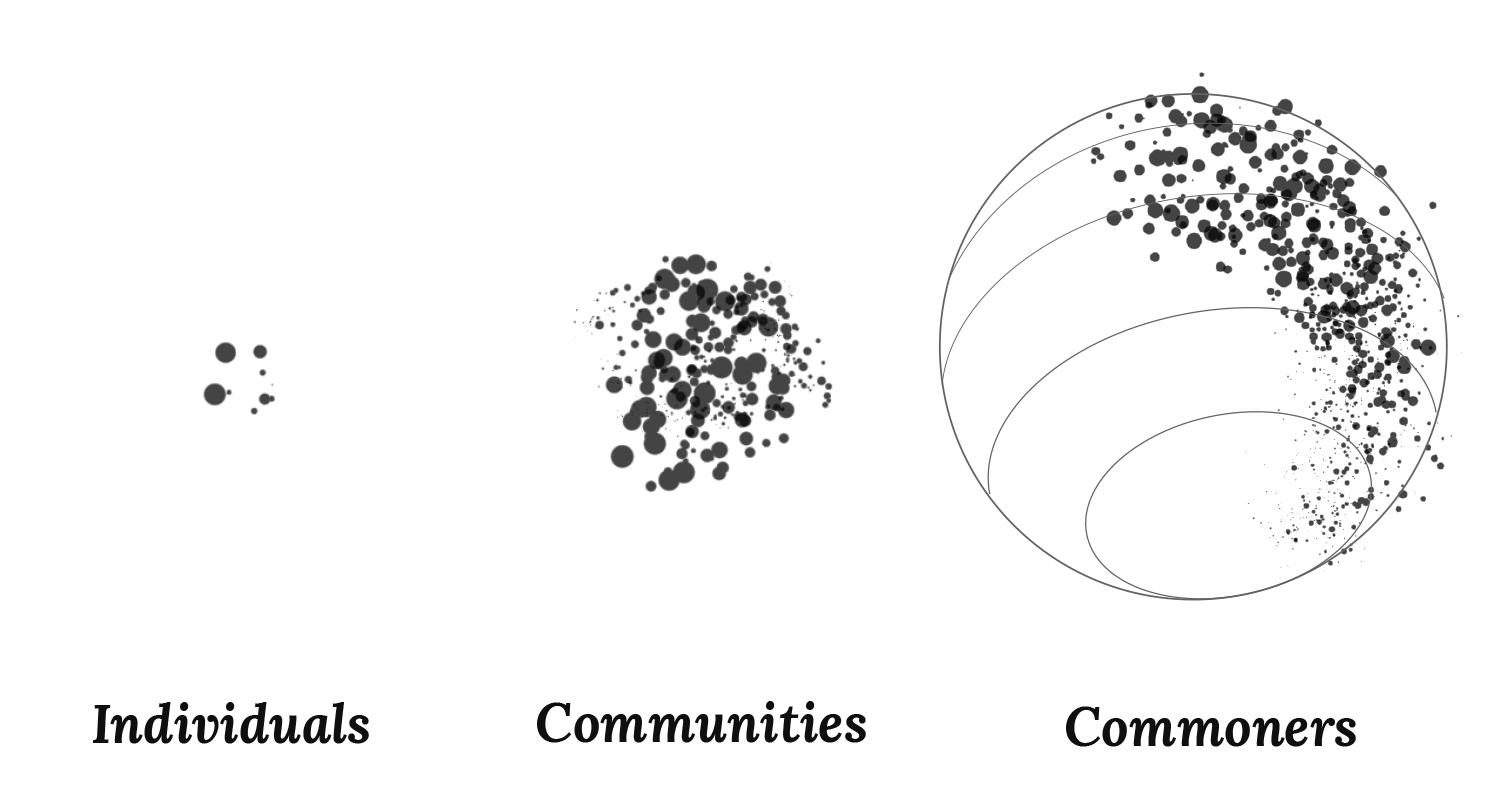

The market/state system often talks about how it performs things for the people — or if participation is allowed, working with the people. But the commons achieves important things through the people. That is to say, ordinary people themselves provide the energy, imagination, and hard work. They do their own provisioning and governance. Commoners are the ones who dream up the systems, devise the rules, provide the expertise, perform the difficult work, monitor for compliance, and deal with rule-breakers.

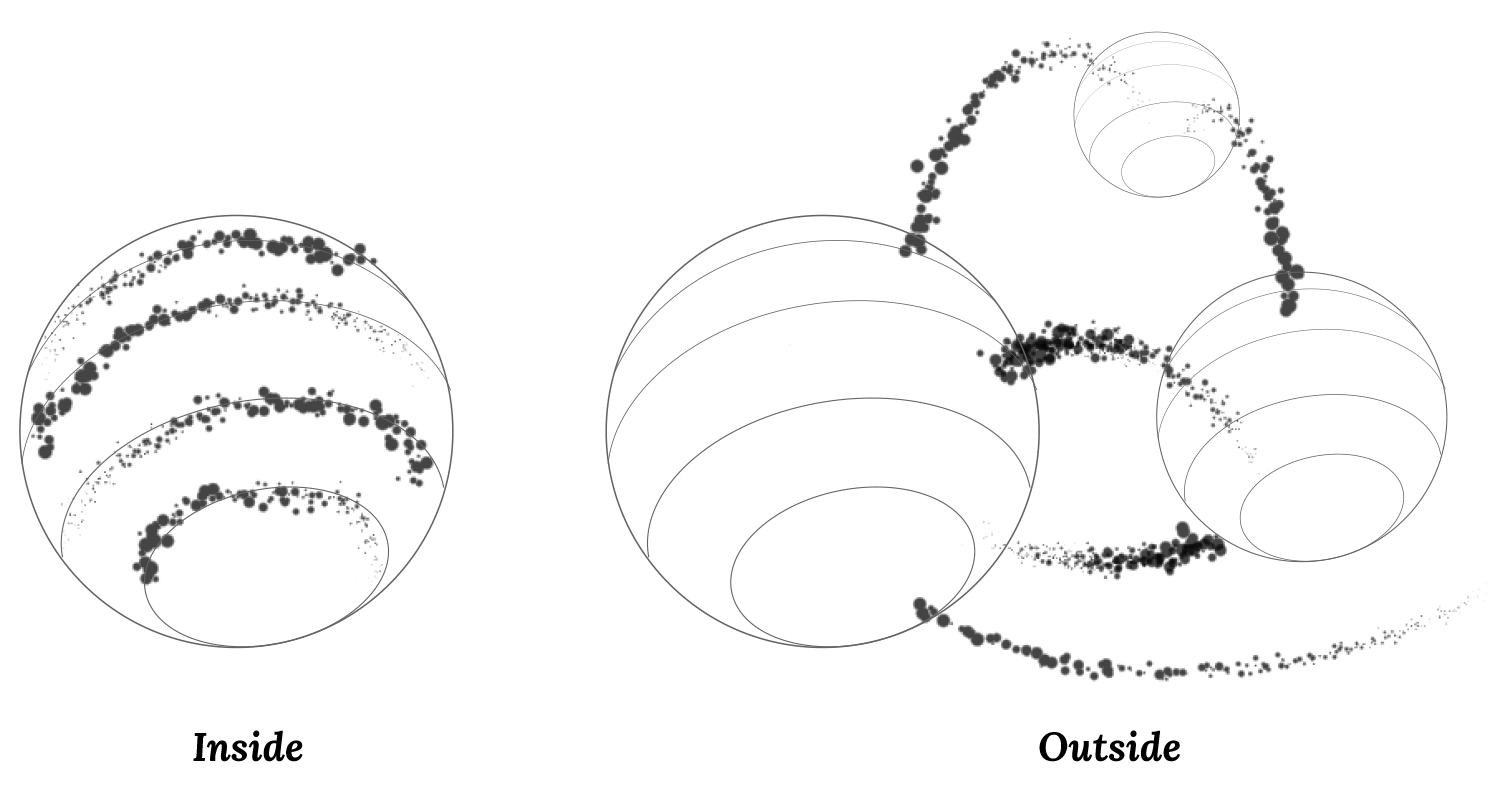

As this implies, the commons involves an identity shift. It requires that people evolve into different roles and perspectives. It demands new ways of relating to other people. It requires that we reassess who matters in our economy and society, and how essential work gets done. Seen from the inside, the commons reveals that we can create value in new ways, and create meaning for ourselves in the process. We can escape from capitalist value chains by creating value networks of mutual commitment. It is by changing the micropatterns of social life, on the ground, with each other, that we can begin to decolonize ourselves from the history and culture into which we were born. We can escape the sense of powerless isolation that defines so much of modern life. We can develop healthier, fair alternatives.

Not surprisingly, the guardians of the prevailing order — in government, business, the media, higher education, philanthropy — prefer to work within existing institutional frameworks. They are content to operate within parochial patterns of thought and puny ideas about human dignity, especially the narrative of progress through economic growth. They prefer that political power be consolidated into centralized structures, such as the nation-state, the corporation, the bureaucracy. This book aims to shatter such presumptions and open up some new vistas of realistic choices.

However, this book is not yet another critique of neoliberal capitalism. While often valuable, even penetrating critiques do not necessarily help us imagine how to remake our institutions and build a new world. What we really need today is creative experimentation and the courage to initiate new patterns of action. We need to learn how to identify patterns of cultural life that can bring about change, notwithstanding the immense power of capital.

For those activists oriented toward political parties and elections, legislation, and policymaking, we counsel a shift to a deeper, more significant level of political life — the world of culture and social practice. Conventional modes of politics working with conventional institutions simply cannot deliver the kinds of change we need. Sixteen-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg has shrewdly observed, “We can’t save the world by playing by the rules.” We need to devise a new set of rules. The old system cannot be ignored, to be sure, and in fact it can often deliver necessary benefits. But we must be honest with ourselves: existing systems will not yield transformational change. That’s why we must be open to bracing winds of change from the periphery, from the unexpected, neglected places, from the zones without pedigree or credentials, from the people themselves.

Accordingly, we refuse to assume that the nation-state is the only realistic system of power for dealing with our fears and offering solutions. It isn’t. The nation-state is, rather, an expression of a fading era. It’s just that respectable circles decline to consider alternatives from the fringe lest they be seen as fuzzy-minded or crazy. But these days, the structural deficiencies of the nation-state and its alliance with capital-driven markets are on vivid display, and can hardly be denied. We have no choice but to abandon our fears — and start to entertain fresh ideas from the margins.

A note of reassurance: “going beyond” the nation-state doesn’t mean “without the nation-state.” It means that we must seriously alter state power by introducing new operational logics and institutional players. Much of this book is devoted to precisely that necessity. We immodestly see commoning as a way to incubate new social practices and cultural logics that are firmly grounded in everyday experience and yet capable of federating themselves to gain strength, cross-fertilizing to grow a new culture, and reaching into the inner councils of state power. When we describe commons and commoning, we are talking about practices that go beyond the usual ways of thinking, speaking, and behaving. One could, therefore, regard this book as a learning guide. We hope to enlarge your understanding of the economy as something that goes beyond the money economy that sets my interest against our interests, and sees the state as the only alternative to the market, for example. This is no small ambition because the market/state has insinuated its premises deep within our consciousness and culture. If we are serious about escaping the stifling logic of capitalism, however, we must probe this deeply. How else can we escape the strange logic by which we first exhaust ourselves and deplete the environment in producing things, and then have to work heroically to repair both, simply so the hamster wheel of the eternal today will continue to turn? How can politicians and citizens possibly take independent initiatives if everything depends on jobs, the stock market, and competition? How can we strike off in new directions when the basic patterns of capitalism constantly inhabit our lives and consciousness, eroding what we have in common? Our aim in writing this book is not just to illuminate new patterns of thought and feeling, but to offer a guide to action.

But how do you begin to approach such a profound change? Our answer is that we must first unravel our understanding of the world: our image of what it means to be a human being, our conception of ownership, prevailing ideas about being and knowing (Chapter 2). When we learn to see the world through a new lens and describe it with new words, a compelling vision comes into focus. We can acquire a new understanding of the good life, our togetherness, the economy, and politics. A semantic revolution of new vocabularies (and the abandonment of old ones) is indispensable for communicating this new vision. That is why, in Chapter 3, we introduce a variety of terms to escape the trap of many misleading binaries (individual/collective, public/private, civilized/premodern) and name the experiences of commoning that currently have no name (Ubuntu rationality, freedom-in-connectedness, value sovereignty, peer governance).

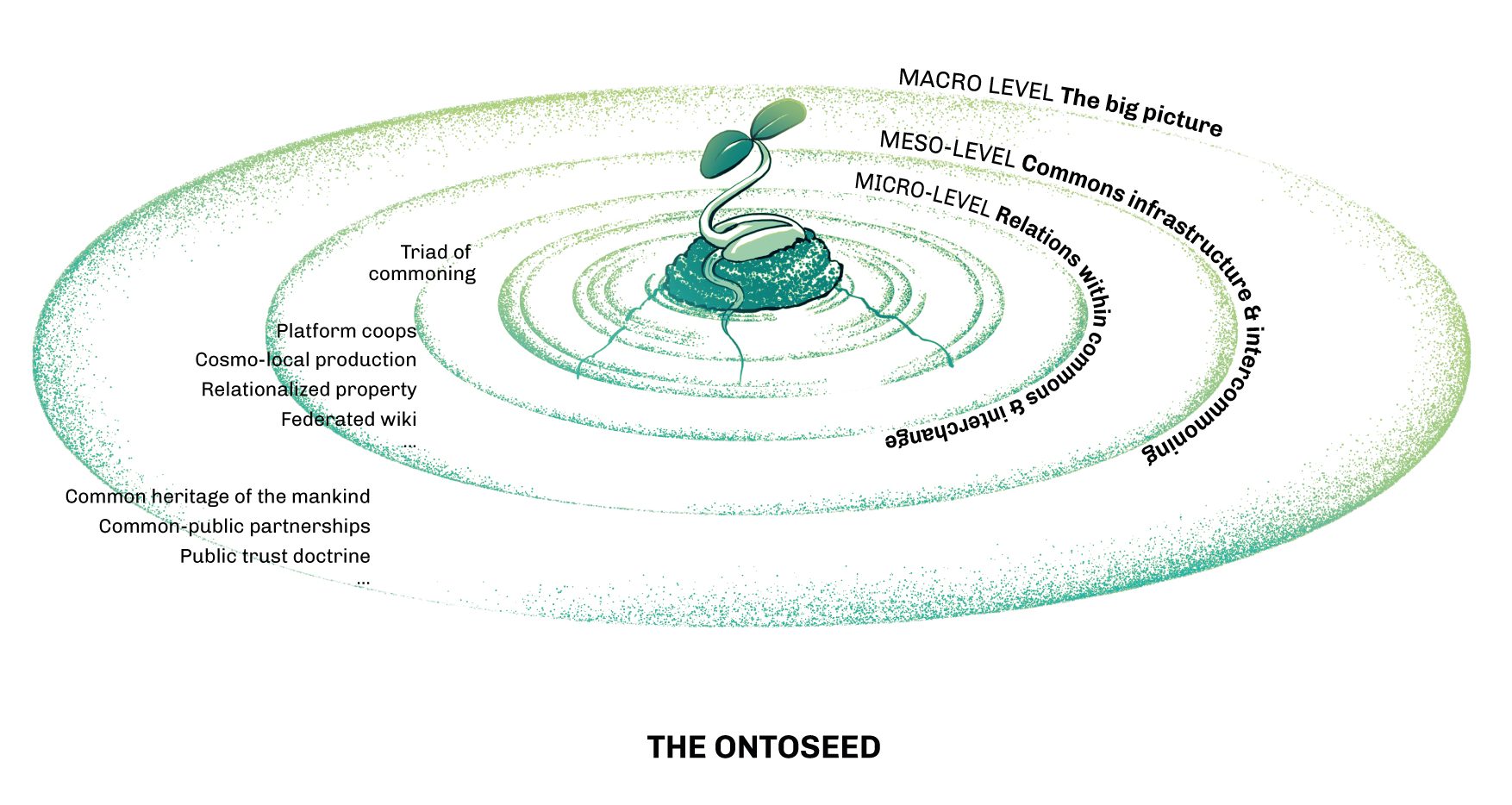

Insights are one thing, meaningful action is another. How then shall we proceed? We regard the “how to do it” section — Part II, consisting of Chapters 4, 5, and 6 — as the heart of the book. The Triad of Commoning, as we call it, systematically describes how the world of the commons “breathes” — how it lives, what its culture feels like. The Triad offers a new framework for understanding and analyzing the commons. The framework itself emerged through a methodology associated with “pattern languages,” in which a process of “patterns mining” is used to identify recurrent patterns of social practice that exist across cultures and history.

This is followed by Part III, which examines the embedded assumptions of property (Chapter 7) and how a new sort of relationalized property can be developed (Chapter 8) to support commoning. We quickly realized that such visions — or other patterns of commoning — tend to run up against state power if they become successful. States are not shy about using law, property rights, state policies, alliances with capital, and coercive practices to advance their vision of the world — which generally frowns upon the realities of commoning. In light of these realities, we outline several general strategies for building the Commonsverse nonetheless (Chapter 9). And we conclude with a look at several specific approaches — commons charters, distributed ledger technologies, commons-public partnerships — that can expand the commons while protecting it against the market/state system (Chapter 10). As a book that seeks to reconceptualize our understanding of commons, we realize that we point to many new avenues of further inquiry that we simply cannot answer here. The greater the shoreline of our knowledge, the greater the oceans of our ignorance. We would have liked to explore a new theory of value to counter the unsatisfactory notions of value, the price system, used by standard economics. The long history of property law contains many fascinating legal doctrines that deserve to be excavated, along with non-Western notions of stewardship and control. The psychological and sociological dimensions of cooperation could illuminate our ideas about commoning with new depth. Scholars of modernity, historians of medieval commons, and anthropologists could help us better understand the social dynamics of the contemporary commons. In short, there is much more to be said about the themes we discuss.

Some of the most salient, understudied big issues involve how commons might mitigate familiar geopolitical, ecological, and humanitarian challenges. Migration, military conflict, climate change, and inequality are all affected by the prevalence of enclosures and the relative strength of commoning. Commoners with stable, locally rooted means of subsistence naturally feel less pressure to flee to wealthier regions of the world. When industrial trawlers destroyed Somali fishery commons, they surely had a role in fueling piracy and terrorism in Africa. Could state protection of commons make a difference? If such provisioning could supplant global market supply chains, it could significantly reduce carbon emissions from transportation and agricultural chemicals. These and many other topics deserve much greater research, analysis, and theorizing.

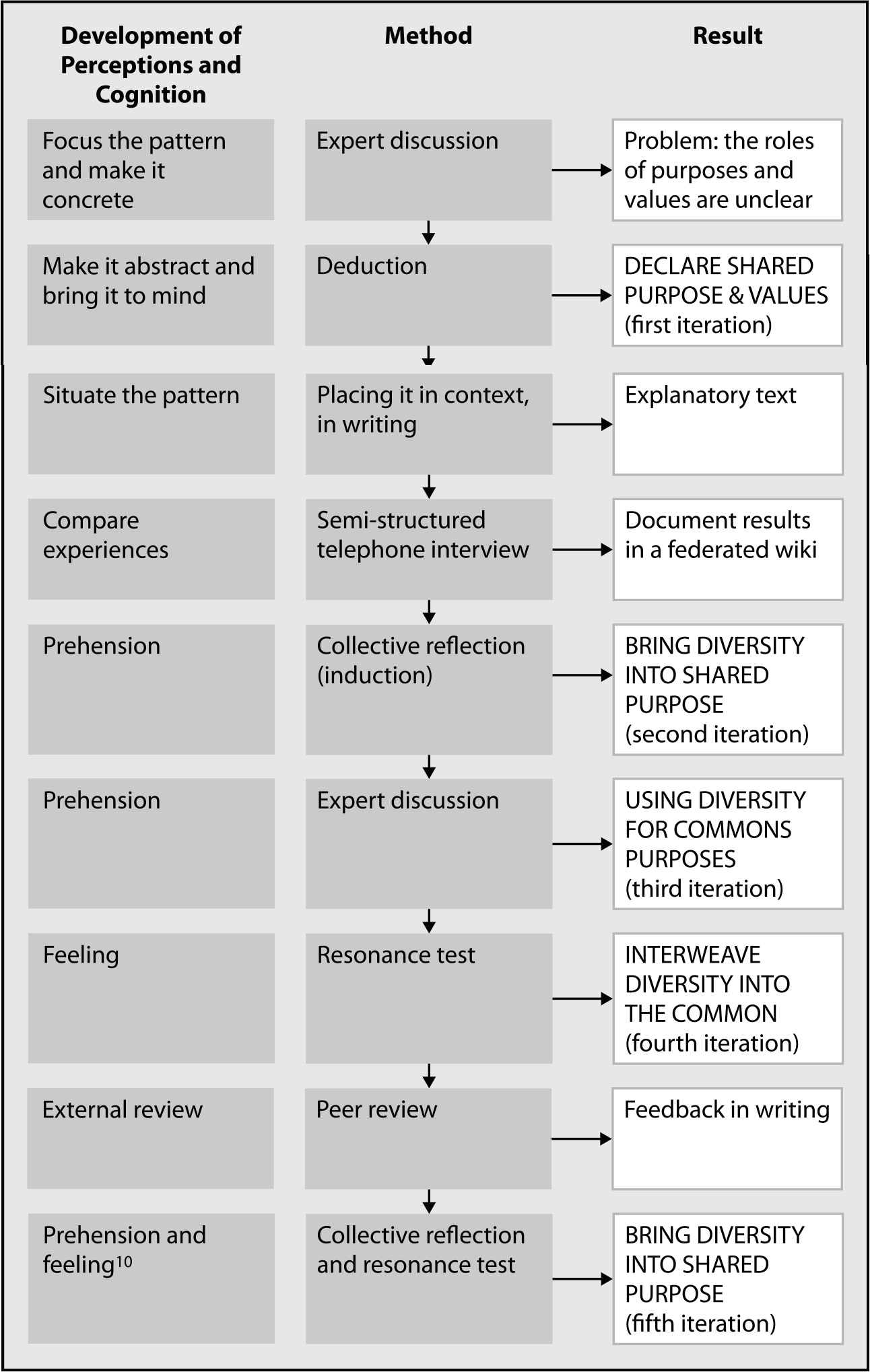

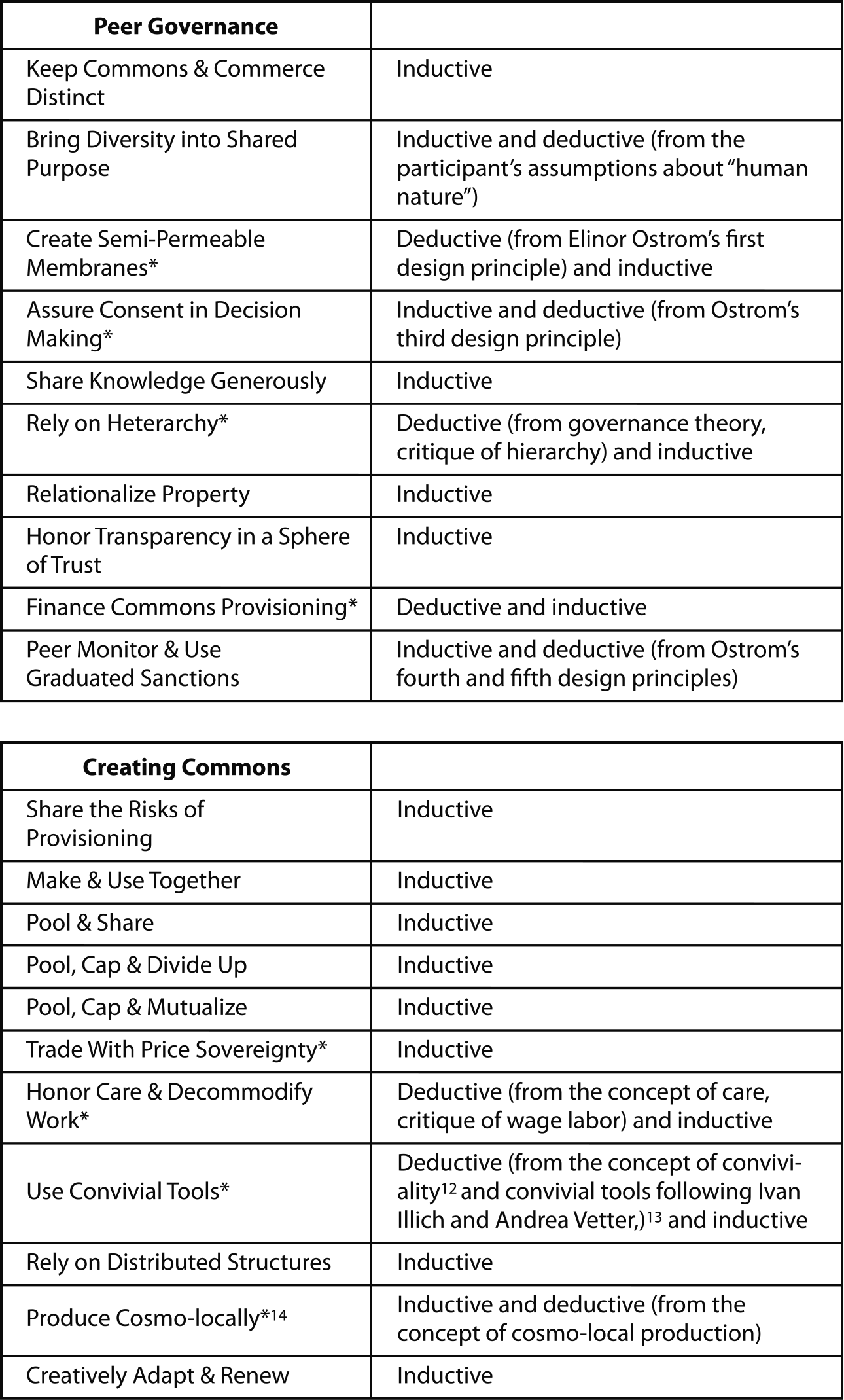

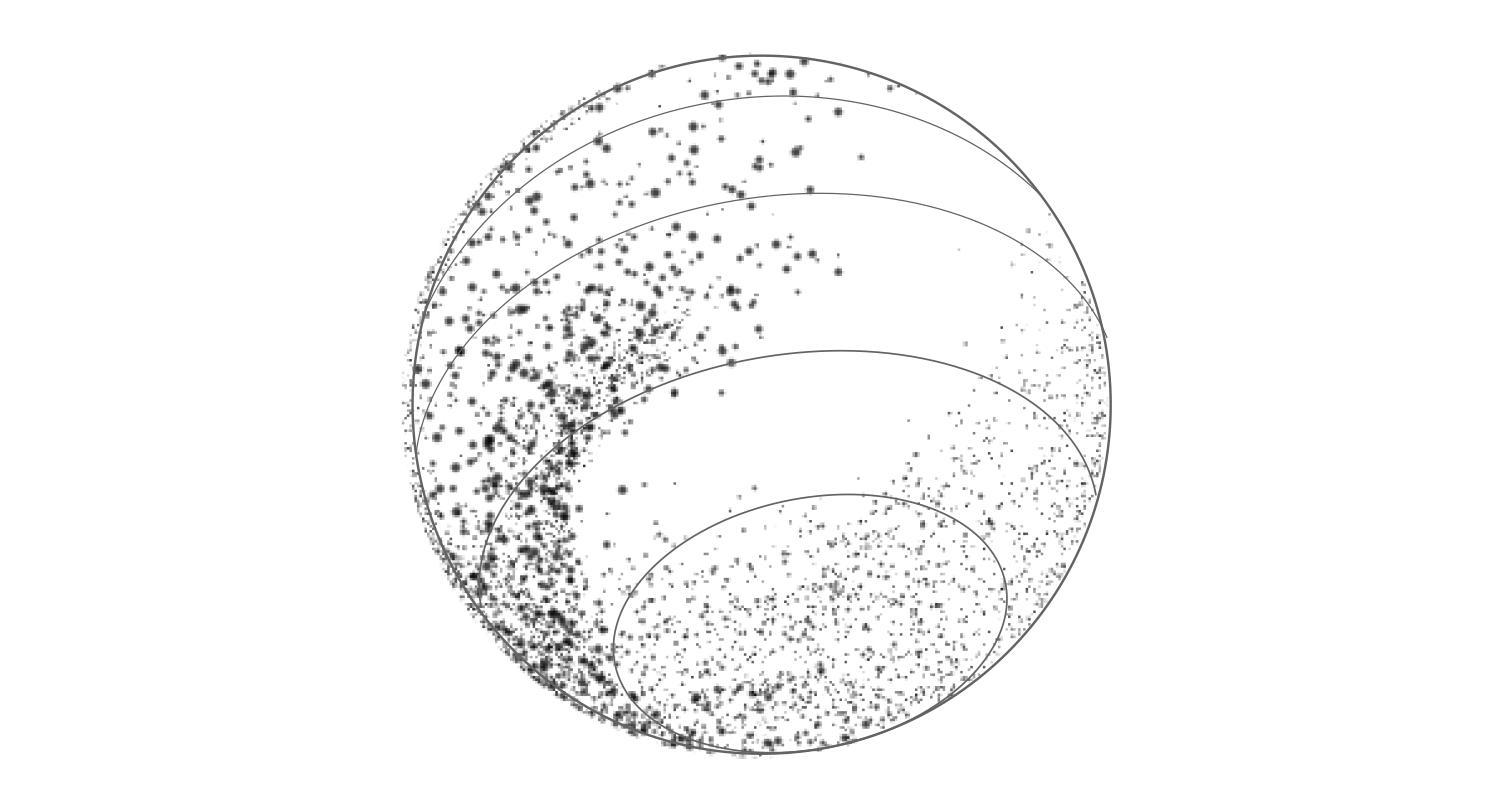

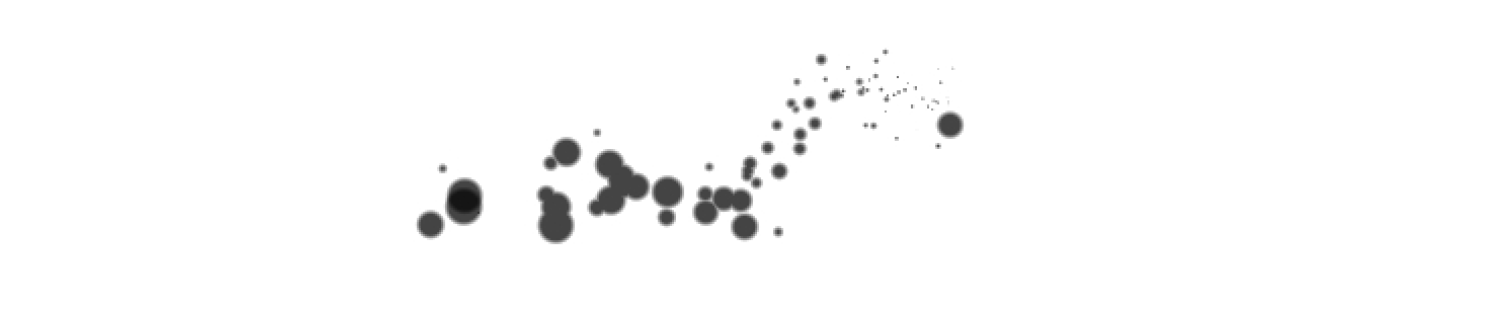

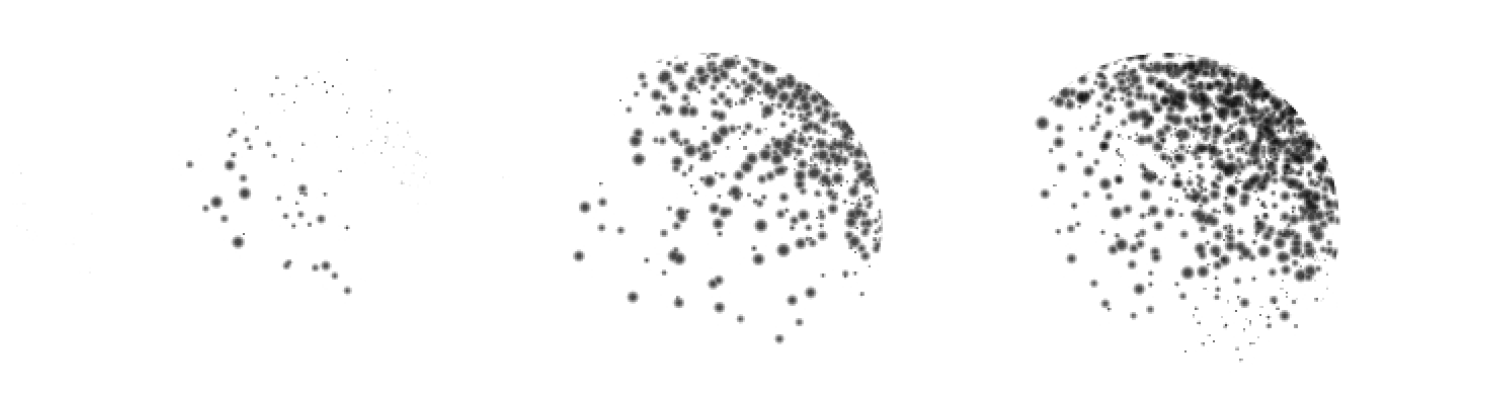

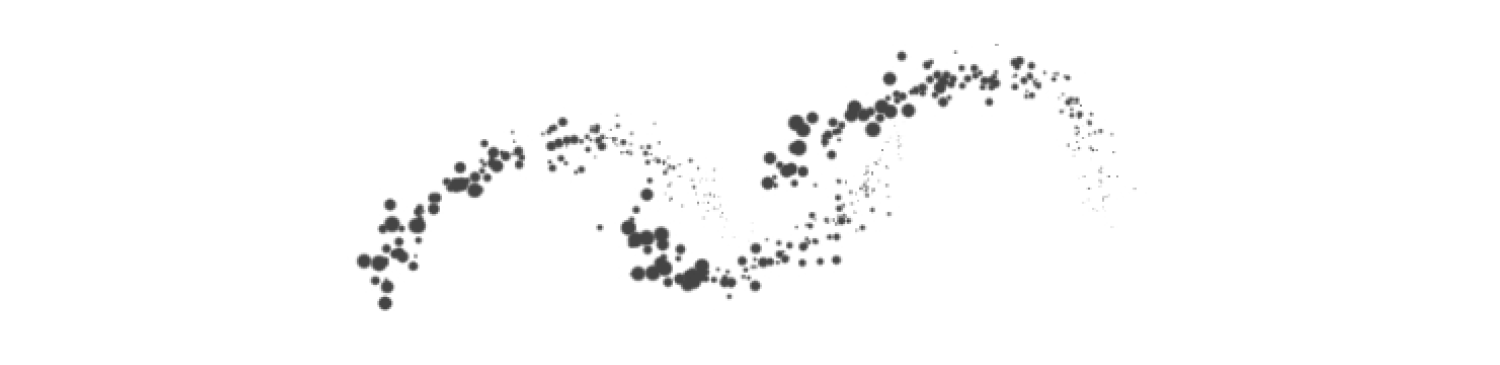

We wish to call attention to four appendices of interest. Appendix A explains the methodology used to identify the patterns of commoning in Part II of the book. Appendix B describes the conceptualization process used by Mercè Moreno Tarrés to draw the twenty-eight beautiful patterns images in Part II. Appendix C lists sixty-nine working commons and tools for commoning mentioned in this book. And Appendix D lists Elinor Ostrom’s eight renowned design principles for effective commons.

Can human beings really learn to cooperate with each other in routine, large-scale ways? A great deal of evidence suggests we can. There is no innate, genetic impediment to cooperation. It’s quite the opposite. In one memorable experiment conducted by developmental and comparative psychologist Michael Tomasello, a bright-eyed toddler watches a man carrying an armful of books as he repeatedly bumps into a closet door. The adult can’t seem to open the closet, and the toddler is concerned. The child spontaneously walks over to the door and opens it, inviting the inept adult to put the books into the closet. In another experiment, an adult repeatedly fails to place a blue tablet on top of an existing stack of tablets. A toddler seated across from the clumsy man grabs the fallen tablets and carefully places each one neatly on the top of the stack. In yet another test, an adult who had been stapling papers in a room leaves, and upon returning with a new set of papers, finds that someone has moved his stapler. A one-year-old infant in the room immediately understands the adult’s problem, and points helpfully at the missing stapler, now on a shelf.

For Tomasello, a core insight came into focus from these and other experiments: human beings instinctively want to help others. In his painstaking attempts to understand the origins of human cooperation, Tomasello and his team have sought to isolate the workings of this human impulse and to differentiate it from the behaviors of other species, especially primates. From years of research, he has concluded that “from around their first birthdays — when they first begin to walk and talk and become truly cultural beings — human children are already cooperative and helpful in many, though obviously not all, situations. And they do not learn this from adults; it comes naturally.”1 Even infants from fourteen to eighteen months of age show the capacity to fetch out-of-reach objects, remove obstacles facing others, correct an adult’s mistake, and choose the correct behaviors for a given task.

Of course, complications arise and multiply as young children grow up. They learn that some people are not trustworthy and that others don’t reciprocate acts of kindness. Children learn to internalize social norms and ethical expectations, especially from societal institutions. As they mature, children associate schooling with economic success, learn to package personal reputation into a marketable brand, and find satisfaction in buying and selling.

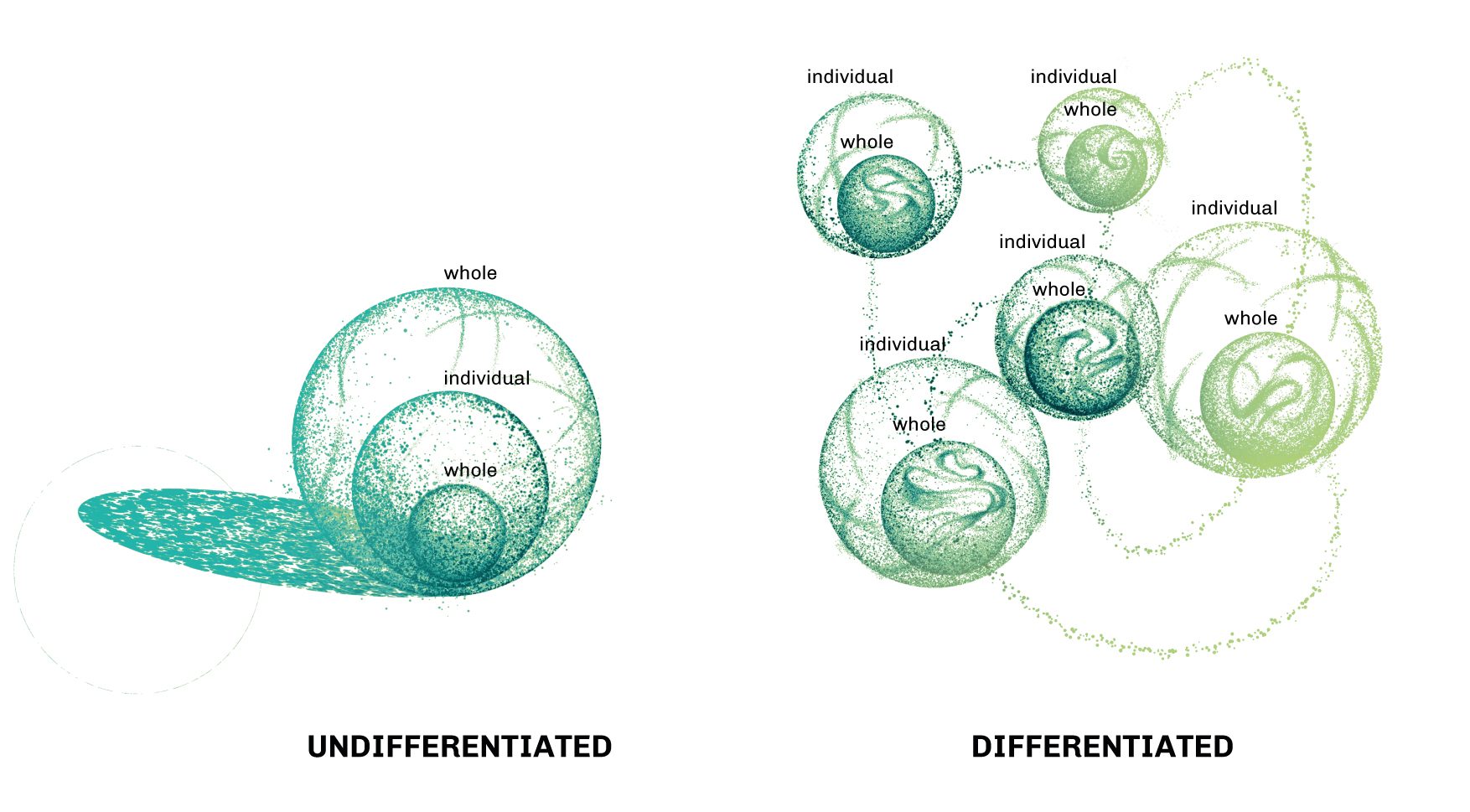

While the drama of acculturation plays out in many different ways, the larger story of the human species is its versatile capacity for cooperation. We have the unique potential to express and act upon shared intentionality. “What makes us [human beings] really different is our ability to put our heads together and to do things that none of us could do alone, to create new resources that we couldn’t create alone,” says Tomasello. “It’s really all about communicating and collaborating and working together.” We are able to do this because we can grasp that other human beings have inner lives with emotions and intentions. We become aware of a shared condition that goes beyond a narrow, self-referential identity. Any individual identity is always, also, part of collective identities that guide how a person thinks, behaves, and solves problems. All of us have been indelibly shaped by our relations with peers and society, and by the language, rituals, and traditions that constitute our cultures. In other words, the conceit that we are “self-made” individuals is a delusion. There is no such thing as an isolated “I.” As we will explore later, each of us is really a Nested-I. We are not only embedded in relationships; our very identities are created through relationships. The Nested-I concept helps us deal more honestly with the encompassing reality of human identity and development. We humans truly are the “cooperative species,” as economists Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis have put it.2 The question is whether or not this deep human instinct will be encouraged to unfold. And if cooperation is encouraged, will it aim to serve all or instead be channeled to serve individualistic, parochial ends?

In our previous books The Wealth of the Commons (2012) and Patterns of Commoning (2015), we documented dozens of notable commons, suggesting that the actual scope and impact of commoning in today’s world is quite large. Our capacity to self-organize to address needs, independent of the state or market, can be seen in community forests, cooperatively run farms and fisheries, open source design and manufacturing communities with global reach, local and regional currencies, and myriad other examples in all realms of life. The elemental human impulse that we are born with — to help others, to improve existing practices — ripens into a stable social form with countless variations: a commons. The impulse to common plays out in the most varied circumstances — impoverished urban neighborhoods, landscapes hit by natural disasters, subsistence farms in the heart of Africa, social networks that come together in cyberspace. And yet, strangely, the commons paradigm is rarely seen as a pervasive social form, perhaps because it so often lives in the shadows of state and market power. It is not recognized as a powerful social force and institutional form in its own right. For us, to talk about the commons is to talk about freedom-in-connectedness — a social space in which we can rediscover and remake ourselves as whole human beings and enjoy some serious measure of self-determination. The discourse around commons and commoning helps us see that individuals working together can bring forth more humane, ethical, and ecologically responsible societies. It is plausible to imagine a stable, supportive post-capitalist order. The very act of commoning, as it expands and registers on the larger culture, catalyzes new political and economic possibilities.

Let us be clear: the commons is not a utopian fantasy. It is something that is happening right now. It can be seen in countless villages and cities, in the Global South and the industrial North, in open source software communities and global cyber-networks. Our first challenge is to name the many acts of commoning in our midst and make them culturally legible. They must be perceived and understood if they are going to be nourished, protected, and expanded. That is the burden of the following chapters and the reason why we propose a new, general framework for understanding commons and commoning.

The commons is not simply about “sharing,” as it happens in countless areas of life. It is about sharing and bringing into being durable social systems for producing shareable things and activities. Nor is the commons about the misleading idea of the “tragedy of the commons.”

This term was popularized by a famous essay by biologist Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” which appeared in the influential journal Science in 1968.3 Paul Ehrlich had just published The Population Bomb, a Malthusian account of a world overwhelmed by sheer numbers of people. In this context, Hardin told a fictional parable of a shared pasture on which no herdsman has a rational incentive to limit the grazing of his cattle. The inevitable result, said Hardin, is that each herdsman will selfishly use as much of the common resource as possible, which will inevitably result in its overuse and ruin — the so-called tragedy of the commons. Possible solutions, Hardin argued, are to grant private property rights to the resource in question, or have the government administer it as public property or on a first-come, first-served basis.

Hardin’s article went on to become the most-cited article in the history of the journal Science, and the phrase “tragedy of the commons” became a cultural buzzword. His fanciful story, endlessly repeated by economists, social scientists, and politicians, has persuaded most people that the commons is a failed management regime. And yet Hardin’s analysis has some remarkable flaws. Most importantly, he was not describing a commons! He was describing a free-for-all in which nothing is owned and everything is free for the taking — an “unmanaged common pool resource,” as some would say. As commons scholar Lewis Hyde has puckishly suggested, Hardin’s “tragedy” thesis ought to be renamed “The Tragedy of Unmanaged, Laissez-Faire, Commons-Pool Resources with Easy Access for Non-Communicating, Self-Interested Individuals.”

In an actual commons, things are different. A distinct community governs a shared resource and its usage. Users negotiate their own rules, assign responsibilities and entitlements, and set up monitoring systems to identify and penalize free riders. To be sure, finite resources can be overexploited, but that outcome is more associated with free markets than with commons. It is no coincidence that our current period of history, in which capitalist markets and private property rights prevail in most places, has produced the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history, an unprecedented loss of fertile soil, disruptions in the hydrologic cycle, and a dangerously warming atmosphere.

As we will see in this book, the commons has so many rich facets that it cannot be easily contained within a single definition. But it helps to clarify how certain terms often associated with the commons are not, in fact, the same as a commons.

Commons are living social systems through which people to address their shared problems in self-organized ways. Unfortunately, some people incorrectly use the term to describe unowned things such as oceans, space, and the moon, or collectively owned resources such as water, forests, and land. As a result, the term commons is frequently conflated with economic concepts that express a very different worldview. Terms such as common goods, common-pool resources, and common property misrepresent the commons because they emphasize objects and individuals, not relationships and systems. Here are some of the misleading terms associated with commons.

Common goods: A term used in neoclassical economy to distinguish among certain types of goods — common goods, club goods, public goods, and private goods. Common goods are said to be difficult to fence off (in economic jargon, they are “nonexcludable”) and susceptible to being used up (“rivalrous”). In other words, common goods tend to get depleted when we share them. Conventional economics presumes that the excludability and depletability of a common good are inherent in the good itself, but this is mistaken. It is not the good that is excludable or not, it’s people who are being excluded or not. A social choice is being made. Similarly, the depletability of a common good has little to do with the good itself, and everything to do with how we choose to make use of water, land, space, or forests. By calling the land, water, or forest a “good,” economists are in fact making a social judgment: they are presuming that something is a resource suitable for market valuation and trade — a presumption that a different culture may wish to reject.

Common-pool resources or CPRs: This term is used by commons scholars, mostly in the tradition of Elinor Ostrom, to analyze how shared resources such as fishing grounds, groundwater basins or grazing areas can be managed. Common-pool resources are regarded as common goods, and in fact usage of the terms is very similar. However, the term common-pool resource is generally invoked to explore how people can use, but not overuse, a shared resource.

Common property: While a CPR refers to a resource as such, common property refers to a system of law that grants formal rights to access or use it. The terms CPR and common good point to a resource itself, for example, whereas common property points to the legal system that regulates how people may use it. Talking about property regimes is thus a very different register of representation than references to water, land, fishing grounds, or software code. Each of these can be managed by any number of different legal regimes; the resource and the legal regime are distinct. Commoners may choose to use a common property regime, but that regime does not constitute the commons.

Common (noun). While some traditionalists use the term “the common” instead of “commons” to refer to shared land or water, cultural theorists Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt introduced a new spin to the term “common” in their 2009 book Commonwealth. They speak of the common to emphasize the social processes that people engage in when cooperating, and to distinguish this idea from the commons as a physical resource. Hardt and Negri note that “the languages we create, the social practices we establish, the modes of sociality that define our relationships” constitute the common. For them, the common is a form of “biopolitical production” that points to a realm beyond property that exists alongside the private and the public, but which unfolds by engaging our affective selves. While this is similar to our use of the term commoning — commons as a verb — the Hardt/Negri uses of the term “common” would seem to include all forms of cooperation, without regard for purpose, and thus could include gangs and the mafia.

The common good: The term, used since the ancient Greeks, refers to positive outcomes for everyone in a society. It is a glittering generality with no clear meaning because virtually all political and economic systems claim that they produce the most benefits for everyone.

The best way to become acquainted with the commons is by learning about a few real-life examples. Therefore, we offer below five short profiles to give a better feel for the contexts of commoning, their specific realities, and their sheer diversity. The examples can help us understand the commons as both a general paradigm of governance, provisioning, and social practice — a worldview and ethic, one might say — and a highly particular phenomenon. Each commons is one of a kind. There are no all-purpose models or “best practices” that define commons and commoning — only suggestive experiences and instructive patterns.

Zaatari Refugee Camp

The Zaatari Refugee camp in Jordan is a settlement of 78,000 displaced Syrians who began to arrive in 2012. The camp may seem like an unlikely illustration of the ideas of this book. Yet in the middle of a desolate landscape, people have devised large and elaborate systems of shelters, neighborhoods, roads, and even a system of addresses. According to Kilian Kleinschmidt, a United Nations official once in charge of the camp, the Zaatari camp in 2015 had “14,000 households, 10,000 sewage pots and private toilets, 3,000 washing machines, 150 private gardens, 3,500 new businesses and shops.”A reporter visiting the camp noted that some of the most elaborate houses there are “cobbled together from shelters, tents, cinder blocks and shipping containers, with interior courtyards, private toilets and jerry-built sewers.” The settlement has a barbershop, a pet store, a flower shop and a home-made ice cream business. There is a pizza delivery service and a travel agency that provides a pickup service at the airport. Zaatari’s main drag is called the Champs-Élysées.5

Of course, Zaatari remains a troubled place with many problems, and the Jordanian state and United Nations remain in charge. But what makes it so notable as a refugee camp is the significant role that self-organized, bottom-up participation has played in building an improvised yet stable city. It is not simply a makeshift survival camp where wretched populations queue up for food, administrators deliver services, and people are treated as helpless victims. It is a place where refugees have been able to apply their own energies and imaginations in building the settlement. They have been able to take some responsibility for self-governance and owning their lives, earning a welcome measure of dignity. You might say that Zaatari administrators and residents, in however partial a way, have recognized the virtues of commoning. The Zaatari experience tells us something about the power of self-organization, a core concept in the commons.

Buurtzorg Nederland

In the Dutch city of Almelo, nurse Jos de Blok was distressed at the steady decline of home care: “Quality was getting worse and worse, the clients’ satisfaction was decreasing, and the expenses were increasing,” he said. De Blok and a small team of professional nurses decided to form a new homecare organization, Buurtzorg Nederland.6 Rather than structure patient care on the model of a factory conveyor belt, delivering measurable units of market services with strict divisions of labor, the home care company relies on small, self-guided teams of highly trained nurses who serve fifty to sixty people in the same neighborhood. (The organization’s name, “Buurtzorg,” is Dutch for “neighborhood care.”) Care is holistic, focusing on a patient’s many personal needs, social circumstances, and long-term condition.

The first thing a nurse usually does when visiting a new patient is to sit down and have a chat and a cup of coffee. As de Blok put it, “People are not bicycles who can be organized according to an organizational chart.” In this respect, Buurtzorg nurses are carrying out the logic of “spending time” (in a commons) as opposed to “saving time” to be more efficient competitors. Interestingly, the emphasis on spending more time with patients results in them needing less professional caretime. If one thinks about it, this is not really a surprise: care-givers basically try to make themselves irrelevant in patients’ lives as quickly as possible, which encourages patients to become more independent. A 2009 study showed that Buurtzorg’s patients get released from care twice as fast as competitors’ clients, and they end up claiming only 50 percent of the prescribed hours of care.7

Nurses provide a full range of assistance to patients, from medical procedures to support services such as bathing. They also identify networks of informal care in a person’s neighborhood, support his or her social life, and promote self-care and independence.8 Buurtzorg is self-managed by nurses. The process is facilitated through a simple, flat organizational structure and information technology, including the use of inspirational blog posts by de Blok. Buurtzorg operates effectively at a large scale without the need for either hierarchy or consensus. In 2017 Buurtzorg employed about 9,000 nurses, who take care of 100,000 patients throughout the Netherlands, with new transnational initiatives underway in the US and Europe.9

It turns out Buurtzorg’s reconceptualization of home healthcare produces high-quality, humane treatment at relatively low costs. By 2015, Buurtzorg care had reduced emergency room visits by 30 percent, according to a KPMG study, and has reduced taxpayer expenditures on home care.10 Buurtzorg also has the most satisfied workforce of any Dutch company with more than 1,000 employees, according to an Ernst & Young study.11

WikiHouse

In 2011, two recent architectural graduates, Alastair Parvin and Nicholas Ierodiaconou, joined a London design practice called Zero Zero Architecture, where they were able to experiment with their ideas about open design. They wondered: What if architects, instead of creating buildings for those who can afford to commission them, helped regular citizens design and build their own houses? This simple idea is at the heart of an astonishing open source construction kit for housing. Parvin and Ierodiaconou learned that a familiar technology known as CNC — computer numerical control fabrication — would enable them to make digital designs that could be used to fabricate large flat pieces from plywood or other material. This led them to develop the idea of publishing open source files for houses, which would let many people modify and improve the designs for different circumstances. It would also allow unskilled labor to quickly and inexpensively erect the structural shell of a home. They called the new design and construction system WikiHouse.12

Since its modest beginnings, WikiHouse has blossomed into a global design community. In 2017 it had eleven chapters in countries around the world, each of which works independently of the original WikiHouse, now a nonprofit foundation that shares the same mission. Simply put, WikiHouse participants want to “put the design solutions for building low-cost, low-energy, high-performance homes into the hands of every citizen and business on earth.” They want to encourage people to Produce Cosmo-Locally, a pattern described in Chapter 6 And they want to “grow a new, distributed housing industry, comprised of many citizens, communities and small businesses developing homes and neighborhoods for themselves, reducing our dependence on top-down, debt-heavy mass housing systems.”

The WikiHouse Charter, a series of fifteen principles, sets forth the basic elements of the technologies, economics, and processes of open source house building. The Charter is one of many examples of how commoners Declare Shared Purpose & Values in developing Peer Governance (see Chapter 5). It includes core ideas such as design standards to lower the thresholds of time, cost, skill, and energy needed to build a house; open standards and open source ShareAlike licenses for design elements; and empowering users to repair and modify features of their homes. By inviting users to adapt designs and tools to serve their own needs, WikiHouse seeks to provide a rich set of “convivial tools,” as described by social critic Ivan Illich. Tools should not attempt to control humans by prescribing narrow ways of doing things. Software should not be burdened with encryption and barriers to repair. Convivial tools are designed to unleash personal creativity and autonomy.13

Community Supported Agriculture

On any Saturday morning in the quiet Massachusetts town of Hadley, you will find families arriving at Next Barn Over farm to pick beans and strawberries from the fields, cut fresh herbs and flowers, and gather their weekly shares of potatoes, kale, onions, radishes, tomatoes, and other produce. Next Barn Over is a CSA farm — Community Supported Agriculture — which means that people buy upfront shares in the farm’s seasonal harvest and then pick up fresh produce weekly from April to November. In other words, CSA members pool the money, before production, and divide up the harvest among all members. This practice, used in thousands of CSAs around the world, inspired us to identify “Pool, Cap & Divide Up” as an important feature of a commons economy (see Chapter 6).

A small share for two people in Next Barn Over costs US$415 while a large share suitable for six people costs US$725. By purchasing shares in the harvest at the beginning of the season, members give farmers the working capital they need and share the risks of production — bad weather, crop diseases, equipment issues. One could say they finance commons provisioning.

A CSA is not primarily a business model, however, because chasing profits is not the point. The point is for families and farmers to mutually support each other in growing healthy food in ecologically responsible ways. All the crops grown on Next Barn Over’s thirty-four acres are organic. Soil fertility is improved through the use of cover crops, organic fertilizers, compost, and manure, with regular crop rotation to reduce pests and disease. The farm uses solar panels from the barn roof. Drip irrigation systems minimize water usage. Next Barn Over also hosts periodic dinners at which families can socialize, dance to local bands’ music, and learn more about the realities of farming in the local ecosystem.

Since the founding of the first CSA in 1986, the idea has grown into an international movement, with more than 1,700 CSAs in the United States alone (2018) and hundreds of others worldwide. While some American CSAs behave almost like businesses, the original philosophy behind CSAs remains strong — to try to develop new forms of cooperation between farmers, workers, and members who are basically consumers. Some are inspired by teikei, a similar model that has been widely used in Japan since the 1970s (The word means “cooperation” or “joint business.”). Here, too, the focus is on smallholder agriculture, organic farming, and direct partnerships between farmers and consumer. One of the founding players in teikei, the Japan Association for Organic Agriculture, has stated its desire “to develop an alternative distribution system that does not depend on conventional markets.”14 The CSA experience is now inspiring a variety of regional agriculture and food distribution projects around the world, with the same end — to empower farmers and ordinary people, strengthen local economies, and avoid the problems caused by Big Agriculture (pesticides, GMOs, additives, processed foods, transport costs). The socio-economic model for CSAs is so solid that the Schumacher Center for a New Economics, which helped incubate the first CSA, is now developing the idea of “community supported industry” for local production. The idea is to use the principles of community mutualization to start and support local businesses — a furniture factory, an applesauce cannery, a humane slaughterhouse — in order to increase local self-reliance.

Guifi.net

Most people assume that only a large cable or telecommunications corporation with political connections and lots of capital can build the infrastructure for Wi-Fi service. The scrappy cooperative Guifi.net of Catalonia has proven that wrong. The enterprise has shown that it is entirely possible for commoners to build and maintain high-quality, affordable internet connections for everyone. By committing itself to principles of mutual ownership, net neutrality, and community control, Guifi.net has grown from a single Wi-Fi node in 2004 to more than 35,000 nodes and 63,000 kilometers of wireless connectivity in July 2018, particularly in rural Catalonia.

Guifi.net got its start when Ramon Roca, a Spanish engineer at Oracle, hacked some off-the-shelf routers. The hack made the routers work as nodes in a mesh network-like system while connected to a single DSL line owned by Telefonica serving municipal governments. This jerry-rigged system enabled people to send and receive internet data using other, similarly hacked routers. As word spread, Roca’s innovation to deal with scarce internet access quickly caught on. As recounted by Wired magazine, Guifi.net grew its system through a kind of improvised crowdfunding system: “‘It was about announcing a plan, describing the cost, and asking for contributions,’ Roca says. The payments weren’t going to Guifi.net, but to the suppliers of gear and ISP [Internet Service Provider] network services. All of these initiatives laid the groundwork not just for building out the overall network, but also creating the array of ISPs.” What Guifi.net did was simply to Pool & Share (see Chapter 6 — it pooled resources and shared internet)

In 2008 Guifi.net established an affiliated foundation to help oversee volunteers, network operations, and governance of the entire system. As Wired described it, the foundation “handled network traffic to and among the providers; connected to the major data ‘interchange’ providing vast amounts of bandwidth between southern Spain and the rest of the world; planned deployment of fiber; and, crucially, developed systems to ensure that the ISPs were paying their fair share of the overall data and network-management costs.”15

Guiding the entire project is a Compact for a Free, Open and Neutral Network, a charter that sets forth the key principles of the Guifi.net commons and the rights and freedoms of users:

Anyone who uses the Guifi.net infrastructure in Catalonia — individual internet users, small businesses, government, dozens of small internet service providers — is committed to “the development of a commons-based, free, open and neutral telecommunications network.” This has resulted in Guifi.net providing far better broadband service at cheaper prices than, say, Americans receive, who pay very high prices to a broadband oligopoly (a median of US$80 month in 2017) for slower connectivity and poor customer service. ISPs using Guifi.net were charging 18 to 35 euros a month in 2016 (roughly US$20–$37) for one gigabit fiber connections, and much lower prices for Wi-Fi. Commons are highly money efficient, as Wolfgang Sachs once pointed out. They enable us to become less reliant on money, and therefore more free from the structural coercion of markets.

Moreover, the Guifi.net experience shows that it is entirely possible to build “large-scale, locally owned, broadband infrastructure in more locations than telco [telephone company] incumbents,” as open technology advocate Sascha Meinrath put it.16 The mutualizing of costs and benefits in a commons regime has a lot to do with this success.

How to make sense of these very different commons? Newcomers to the topic often throw up their hands in confusion because they cannot readily see the deeper patterns that make a commons a commons. They find it perplexing that so many diverse phenomena can be described by the same term. This problem is really a matter of training one’s perception. Everyone is familiar with the “free market” even though its variations — stock markets, grocery stores, filmmaking, mining, personal services, labor — are at least as eclectic as the commons. But culturally, we regard the diversity of markets as normal whereas commons are nearly invisible.

The strange truth is that a popular language for understanding contemporary commons is almost entirely absent. Social science scholarship on the topic is often obscure and highly specialized, and the economic literature tends to treat commons as physical resources, not as social systems. But rather than focus on the resource that each depends on, it makes more sense to focus on the ways in which each is similar. Each commons depends on social processes, the sharing of knowledge, and physical resources. Each shares challenges in bringing together the social, the political (governance), and the economic (provisioning) into an integrated whole.

So a big part of our challenge is to recover the neglected social history of commons and learn how it applies to contemporary circumstances. This requires a conceptual framework, new language, and stories that anyone can understand. Explaining the commons with the vocabulary of capital, business, and standard economics cannot work. It is like using the metaphors of clockworks and machines to explain complex living systems. To learn how commons actually work, we need to escape deeply rooted habits of thought and cultivate some fresh perspectives.

This task becomes easier once we realize that there is no single, universal template for assessing a commons. Each bears the distinctive marks of its own special origins, culture, people, and context. Yet there are also many deep, recurrent patterns of commoning that allow us to make some careful generalizations. Commons that superficially appear quite different often have remarkable similarities in how they govern themselves, divide up resources, protect themselves against enclosure, and cultivate shared intentionality. In other words, commons are not standardized machines that can be built from the same blueprint. They are living systems that evolve, adapt over time, and surprise us with their creativity and scope.

The word “patterns” as we use it here deserves a bit of explanation. Our usage derives from the ideas developed by architect and philosopher Christopher Alexander in his celebrated 1977 book A Pattern Language — ideas that are further elaborated on in his four-volume masterwork, The Nature of Order, the result of twenty-seven years of research and original thinking. Alexander and his co-authors brilliantly blend an empirical scientific perspective with ideas about the formative role of beauty and grace in everyday life and design, resulting in what we would call “enlivenment.”17

In Alexander’s view, a pattern describes “a problem that occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.”18 In other words, patterns-thinking and solutions based on it are never decontextualized, nor disconnected from what we think and feel. We suggest looking closely at the underlying patterns of thriving social processes for inspiration while keeping in mind that a successful commons cannot be copied and pasted. Each must develop its own appropriate localized, context-specific solutions. Each must satisfy practical needs and deeper human aspirations and interests.

In this volume, we attempt to identify the patterns that are building a growing constellation of commons around the world — the Commonsverse. In our account of this realm, we are both descriptive and aspirational — descriptive in assessing how diverse commons function, and aspirational in trying to imagine how the known commoning dynamics could plausibly grow and become a distinct sector of the political economy and culture. We draw on the social sciences to discuss important aspects of the commons. But we also draw upon our own extensive firsthand experiences in talking with commoners and learning about their remarkable communities. We wish to describe a rich, textured field of human creativity and social organization that has been overlooked for too long, while reassuring the reader that commons are not so complicated and obscure that only professionals can grasp them. In fact, they arise from common people doing fairly common things that only seem uncommon in market-oriented societies.

In the course of our travels, we have been astonished at the remarkable range of circumstances in which commoning occurs. This has led us to wonder: Why do so many discussions about commons rely on economic categories of analysis (“types of goods,” “resource allocation,” “productivity,” “transaction costs”) when commons are primarily social systems for meeting shared needs? This question propelled us on a process to reconceptualize in its fullest sense what it means to engage in commoning.

We think that such a perspective contributes to a broader paradigm shift. It helps us to redefine the very idea of the economy and enlarge the functional scope of democratic action. Commons meet real needs while changing culture and identity. They influence our social practices, ethics, and worldviews and in so doing change the very character of politics. To understand these deeper currents, we need a richer framework for making sense of the commons. We need it to better explain the internal dynamics of peer governance and provisioning — and also the ways in which commoning connects the larger political economy and our inner lives. In short, we must see that the commons requires a new worldview.

Can human beings really learn to cooperate with each other in routine, large-scale ways? A great deal of evidence suggests we can. There is no innate, genetic impediment to cooperation. It’s quite the opposite. In one memorable experiment conducted by developmental and comparative psychologist Michael Tomasello, a bright-eyed toddler watches a man carrying an armful of books as he repeatedly bumps into a closet door. The adult can’t seem to open the closet, and the toddler is concerned. The child spontaneously walks over to the door and opens it, inviting the inept adult to put the books into the closet. In another experiment, an adult repeatedly fails to place a blue tablet on top of an existing stack of tablets. A toddler seated across from the clumsy man grabs the fallen tablets and carefully places each one neatly on the top of the stack. In yet another test, an adult who had been stapling papers in a room leaves, and upon returning with a new set of papers, finds that someone has moved his stapler. A one-year-old infant in the room immediately understands the adult’s problem, and points helpfully at the missing stapler, now on a shelf.

For Tomasello, a core insight came into focus from these and other experiments: human beings instinctively want to help others. In his painstaking attempts to understand the origins of human cooperation, Tomasello and his team have sought to isolate the workings of this human impulse and to differentiate it from the behaviors of other species, especially primates. From years of research, he has concluded that “from around their first birthdays — when they first begin to walk and talk and become truly cultural beings — human children are already cooperative and helpful in many, though obviously not all, situations. And they do not learn this from adults; it comes naturally.”1 Even infants from fourteen to eighteen months of age show the capacity to fetch out-of-reach objects, remove obstacles facing others, correct an adult’s mistake, and choose the correct behaviors for a given task.

Of course, complications arise and multiply as young children grow up. They learn that some people are not trustworthy and that others don’t reciprocate acts of kindness. Children learn to internalize social norms and ethical expectations, especially from societal institutions. As they mature, children associate schooling with economic success, learn to package personal reputation into a marketable brand, and find satisfaction in buying and selling.

While the drama of acculturation plays out in many different ways, the larger story of the human species is its versatile capacity for cooperation. We have the unique potential to express and act upon shared intentionality. “What makes us [human beings] really different is our ability to put our heads together and to do things that none of us could do alone, to create new resources that we couldn’t create alone,” says Tomasello. “It’s really all about communicating and collaborating and working together.” We are able to do this because we can grasp that other human beings have inner lives with emotions and intentions. We become aware of a shared condition that goes beyond a narrow, self-referential identity. Any individual identity is always, also, part of collective identities that guide how a person thinks, behaves, and solves problems. All of us have been indelibly shaped by our relations with peers and society, and by the language, rituals, and traditions that constitute our cultures. In other words, the conceit that we are “self-made” individuals is a delusion. There is no such thing as an isolated “I.” As we will explore later, each of us is really a Nested-I. We are not only embedded in relationships; our very identities are created through relationships. The Nested-I concept helps us deal more honestly with the encompassing reality of human identity and development. We humans truly are the “cooperative species,” as economists Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis have put it.2 The question is whether or not this deep human instinct will be encouraged to unfold. And if cooperation is encouraged, will it aim to serve all or instead be channeled to serve individualistic, parochial ends?

In our previous books The Wealth of the Commons (2012) and Patterns of Commoning (2015), we documented dozens of notable commons, suggesting that the actual scope and impact of commoning in today’s world is quite large. Our capacity to self-organize to address needs, independent of the state or market, can be seen in community forests, cooperatively run farms and fisheries, open source design and manufacturing communities with global reach, local and regional currencies, and myriad other examples in all realms of life. The elemental human impulse that we are born with — to help others, to improve existing practices — ripens into a stable social form with countless variations: a commons. The impulse to common plays out in the most varied circumstances — impoverished urban neighborhoods, landscapes hit by natural disasters, subsistence farms in the heart of Africa, social networks that come together in cyberspace. And yet, strangely, the commons paradigm is rarely seen as a pervasive social form, perhaps because it so often lives in the shadows of state and market power. It is not recognized as a powerful social force and institutional form in its own right. For us, to talk about the commons is to talk about freedom-in-connectedness — a social space in which we can rediscover and remake ourselves as whole human beings and enjoy some serious measure of self-determination. The discourse around commons and commoning helps us see that individuals working together can bring forth more humane, ethical, and ecologically responsible societies. It is plausible to imagine a stable, supportive post-capitalist order. The very act of commoning, as it expands and registers on the larger culture, catalyzes new political and economic possibilities.

Let us be clear: the commons is not a utopian fantasy. It is something that is happening right now. It can be seen in countless villages and cities, in the Global South and the industrial North, in open source software communities and global cyber-networks. Our first challenge is to name the many acts of commoning in our midst and make them culturally legible. They must be perceived and understood if they are going to be nourished, protected, and expanded. That is the burden of the following chapters and the reason why we propose a new, general framework for understanding commons and commoning.

The commons is not simply about “sharing,” as it happens in countless areas of life. It is about sharing and bringing into being durable social systems for producing shareable things and activities. Nor is the commons about the misleading idea of the “tragedy of the commons.”

This term was popularized by a famous essay by biologist Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” which appeared in the influential journal Science in 1968.3 Paul Ehrlich had just published The Population Bomb, a Malthusian account of a world overwhelmed by sheer numbers of people. In this context, Hardin told a fictional parable of a shared pasture on which no herdsman has a rational incentive to limit the grazing of his cattle. The inevitable result, said Hardin, is that each herdsman will selfishly use as much of the common resource as possible, which will inevitably result in its overuse and ruin — the so-called tragedy of the commons. Possible solutions, Hardin argued, are to grant private property rights to the resource in question, or have the government administer it as public property or on a first-come, first-served basis.

Hardin’s article went on to become the most-cited article in the history of the journal Science, and the phrase “tragedy of the commons” became a cultural buzzword. His fanciful story, endlessly repeated by economists, social scientists, and politicians, has persuaded most people that the commons is a failed management regime. And yet Hardin’s analysis has some remarkable flaws. Most importantly, he was not describing a commons! He was describing a free-for-all in which nothing is owned and everything is free for the taking — an “unmanaged common pool resource,” as some would say. As commons scholar Lewis Hyde has puckishly suggested, Hardin’s “tragedy” thesis ought to be renamed “The Tragedy of Unmanaged, Laissez-Faire, Commons-Pool Resources with Easy Access for Non-Communicating, Self-Interested Individuals.”

In an actual commons, things are different. A distinct community governs a shared resource and its usage. Users negotiate their own rules, assign responsibilities and entitlements, and set up monitoring systems to identify and penalize free riders. To be sure, finite resources can be overexploited, but that outcome is more associated with free markets than with commons. It is no coincidence that our current period of history, in which capitalist markets and private property rights prevail in most places, has produced the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history, an unprecedented loss of fertile soil, disruptions in the hydrologic cycle, and a dangerously warming atmosphere.

As we will see in this book, the commons has so many rich facets that it cannot be easily contained within a single definition. But it helps to clarify how certain terms often associated with the commons are not, in fact, the same as a commons.

Commons are living social systems through which people to address their shared problems in self-organized ways. Unfortunately, some people incorrectly use the term to describe unowned things such as oceans, space, and the moon, or collectively owned resources such as water, forests, and land. As a result, the term commons is frequently conflated with economic concepts that express a very different worldview. Terms such as common goods, common-pool resources, and common property misrepresent the commons because they emphasize objects and individuals, not relationships and systems. Here are some of the misleading terms associated with commons.

Common goods: A term used in neoclassical economy to distinguish among certain types of goods — common goods, club goods, public goods, and private goods. Common goods are said to be difficult to fence off (in economic jargon, they are “nonexcludable”) and susceptible to being used up (“rivalrous”). In other words, common goods tend to get depleted when we share them. Conventional economics presumes that the excludability and depletability of a common good are inherent in the good itself, but this is mistaken. It is not the good that is excludable or not, it’s people who are being excluded or not. A social choice is being made. Similarly, the depletability of a common good has little to do with the good itself, and everything to do with how we choose to make use of water, land, space, or forests. By calling the land, water, or forest a “good,” economists are in fact making a social judgment: they are presuming that something is a resource suitable for market valuation and trade — a presumption that a different culture may wish to reject.

Common-pool resources or CPRs: This term is used by commons scholars, mostly in the tradition of Elinor Ostrom, to analyze how shared resources such as fishing grounds, groundwater basins or grazing areas can be managed. Common-pool resources are regarded as common goods, and in fact usage of the terms is very similar. However, the term common-pool resource is generally invoked to explore how people can use, but not overuse, a shared resource.

Common property: While a CPR refers to a resource as such, common property refers to a system of law that grants formal rights to access or use it. The terms CPR and common good point to a resource itself, for example, whereas common property points to the legal system that regulates how people may use it. Talking about property regimes is thus a very different register of representation than references to water, land, fishing grounds, or software code. Each of these can be managed by any number of different legal regimes; the resource and the legal regime are distinct. Commoners may choose to use a common property regime, but that regime does not constitute the commons.

Common (noun). While some traditionalists use the term “the common” instead of “commons” to refer to shared land or water, cultural theorists Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt introduced a new spin to the term “common” in their 2009 book Commonwealth. They speak of the common to emphasize the social processes that people engage in when cooperating, and to distinguish this idea from the commons as a physical resource. Hardt and Negri note that “the languages we create, the social practices we establish, the modes of sociality that define our relationships” constitute the common. For them, the common is a form of “biopolitical production” that points to a realm beyond property that exists alongside the private and the public, but which unfolds by engaging our affective selves. While this is similar to our use of the term commoning — commons as a verb — the Hardt/ Negri uses of the term “common” would seem to include all forms of cooperation, without regard for purpose, and thus could include gangs and the mafia.

The common good: The term, used since the ancient Greeks, refers to positive outcomes for everyone in a society. It is a glittering generality with no clear meaning because virtually all political and economic systems claim that they produce the most benefits for everyone.

The best way to become acquainted with the commons is by learning about a few real-life examples. Therefore, we offer below five short profiles to give a better feel for the contexts of commoning, their specific realities, and their sheer diversity. The examples can help us understand the commons as both a general paradigm of governance, provisioning, and social practice — a worldview and ethic, one might say — and a highly particular phenomenon. Each commons is one of a kind. There are no all-purpose models or “best practices” that define commons and commoning — only suggestive experiences and instructive patterns.

Zaatari Refugee Camp

The Zaatari Refugee camp in Jordan is a settlement of 78,000 displaced Syrians who began to arrive in 2012. The camp may seem like an unlikely illustration of the ideas of this book. Yet in the middle of a desolate landscape, people have devised large and elaborate systems of shelters, neighborhoods, roads, and even a system of addresses. According to Kilian Kleinschmidt, a United Nations official once in charge of the camp, the Zaatari camp in 2015 had “14,000 households, 10,000 sewage pots and private toilets, 3,000 washing machines, 150 private gardens, 3,500 new businesses and shops.”A reporter visiting the camp noted that some of the most elaborate houses there are “cobbled together from shelters, tents, cinder blocks and shipping containers, with interior courtyards, private toilets and jerry-built sewers.” The settlement has a barbershop, a pet store, a flower shop and a homemade ice cream business. There is a pizza delivery service and a travel agency that provides a pickup service at the airport. Zaatari’s main drag is called the Champs-Élysées.5

Of course, Zaatari remains a troubled place with many problems, and the Jordanian state and United Nations remain in charge. But what makes it so notable as a refugee camp is the significant role that self-organized, bottom-up participation has played in building an improvised yet stable city. It is not simply a makeshift survival camp where wretched populations queue up for food, administrators deliver services, and people are treated as helpless victims. It is a place where refugees have been able to apply their own energies and imaginations in building the settlement. They have been able to take some responsibility for self-governance and owning their lives, earning a welcome measure of dignity. You might say that Zaatari administrators and residents, in however partial a way, have recognized the virtues of commoning. The Zaatari experience tells us something about the power of self-organization, a core concept in the commons.

Buurtzorg Nederland

In the Dutch city of Almelo, nurse Jos de Blok was distressed at the steady decline of home care: “Quality was getting worse and worse, the clients’ satisfaction was decreasing, and the expenses were increasing,” he said. De Blok and a small team of professional nurses decided to form a new homecare organization, Buurtzorg Nederland.6 Rather than structure patient care on the model of a factory conveyor belt, delivering measurable units of market services with strict divisions of labor, the home care company relies on small, self-guided teams of highly trained nurses who serve fifty to sixty people in the same neighborhood. (The organization’s name, “Buurtzorg,” is Dutch for “neighborhood care.”) Care is holistic, focusing on a patient’s many personal needs, social circumstances, and long-term condition.

The first thing a nurse usually does when visiting a new patient is to sit down and have a chat and a cup of coffee. As de Blok put it, “People are not bicycles who can be organized according to an organizational chart.” In this respect, Buurtzorg nurses are carrying out the logic of “spending time” (in a commons) as opposed to “saving time” to be more efficient competitors. Interestingly, the emphasis on spending more time with patients results in them needing less professional caretime. If one thinks about it, this is not really a surprise: care-givers basically try to make themselves irrelevant in patients’ lives as quickly as possible, which encourages patients to become more independent. A 2009 study showed that Buurtzorg’s patients get released from care twice as fast as competitors’ clients, and they end up claiming only 50 percent of the prescribed hours of care.7

Nurses provide a full range of assistance to patients, from medical procedures to support services such as bathing. They also identify networks of informal care in a person’s neighborhood, support his or her social life, and promote self-care and independence.8 Buurtzorg is self-managed by nurses. The process is facilitated through a simple, flat organizational structure and information technology, including the use of inspirational blog posts by de Blok. Buurtzorg operates effectively at a large scale without the need for either hierarchy or consensus. In 2017 Buurtzorg employed about 9,000 nurses, who take care of 100,000 patients throughout the Netherlands, with new transnational initiatives underway in the US and Europe.9

It turns out Buurtzorg’s reconceptualization of home healthcare produces high-quality, humane treatment at relatively low costs. By 2015, Buurtzorg care had reduced emergency room visits by 30 percent, according to a KPMG study, and has reduced taxpayer expenditures on home care.10 Buurtzorg also has the most satisfied workforce of any Dutch company with more than 1,000 employees, according to an Ernst & Young study.11

WikiHouse

In 2011, two recent architectural graduates, Alastair Parvin and Nicholas Ierodiaconou, joined a London design practice called Zero Zero Architecture, where they were able to experiment with their ideas about open design. They wondered: What if architects, instead of creating buildings for those who can afford to commission them, helped regular citizens design and build their own houses? This simple idea is at the heart of an astonishing open source construction kit for housing. Parvin and Ierodiaconou learned that a familiar technology known as CNC — computer numerical control fabrication — would enable them to make digital designs that could be used to fabricate large flat pieces from plywood or other material. This led them to develop the idea of publishing open source files for houses, which would let many people modify and improve the designs for different circumstances. It would also allow unskilled labor to quickly and inexpensively erect the structural shell of a home. They called the new design and construction system WikiHouse.12

Since its modest beginnings, WikiHouse has blossomed into a global design community. In 2017 it had eleven chapters in countries around the world, each of which works independently of the original WikiHouse, now a nonprofit foundation that shares the same mission. Simply put, WikiHouse participants want to “put the design solutions for building low-cost, low-energy, high-performance homes into the hands of every citizen and business on earth.” They want to encourage people to Produce Cosmo-Locally, a pattern described in Chapter 6 And they want to “grow a new, distributed housing industry, comprised of many citizens, communities and small businesses developing homes and neighborhoods for themselves, reducing our dependence on top-down, debt-heavy mass housing systems.”

The WikiHouse Charter, a series of fifteen principles, sets forth the basic elements of the technologies, economics, and processes of open source house building. The Charter is one of many examples of how commoners Declare Shared Purpose & Values in developing Peer Governance (see Chapter 5). It includes core ideas such as design standards to lower the thresholds of time, cost, skill, and energy needed to build a house; open standards and open source ShareAlike licenses for design elements; and empowering users to repair and modify features of their homes. By inviting users to adapt designs and tools to serve their own needs, WikiHouse seeks to provide a rich set of “convivial tools,” as described by social critic Ivan Illich. Tools should not attempt to control humans by prescribing narrow ways of doing things. Software should not be burdened with encryption and barriers to repair. Convivial tools are designed to unleash personal creativity and autonomy.13

Community Supported Agriculture

On any Saturday morning in the quiet Massachusetts town of Hadley, you will find families arriving at Next Barn Over farm to pick beans and strawberries from the fields, cut fresh herbs and flowers, and gather their weekly shares of potatoes, kale, onions, radishes, tomatoes, and other produce. Next Barn Over is a CSA farm — Community Supported Agriculture — which means that people buy upfront shares in the farm’s seasonal harvest and then pick up fresh produce weekly from April to November. In other words, CSA members pool the money, before production, and divide up the harvest among all members. This practice, used in thousands of CSAs around the world, inspired us to identify “Pool, Cap & Divide Up” as an important feature of a commons economy (see Chapter 6).

A small share for two people in Next Barn Over costs US$415 while a large share suitable for six people costs US$725. By purchasing shares in the harvest at the beginning of the season, members give farmers the working capital they need and share the risks of production — bad weather, crop diseases, equipment issues. One could say they finance commons provisioning.

A CSA is not primarily a business model, however, because chasing profits is not the point. The point is for families and farmers to mutually support each other in growing healthy food in ecologically responsible ways. All the crops grown on Next Barn Over’s thirty-four acres are organic. Soil fertility is improved through the use of cover crops, organic fertilizers, compost, and manure, with regular crop rotation to reduce pests and disease. The farm uses solar panels from the barn roof. Drip irrigation systems minimize water usage. Next Barn Over also hosts periodic dinners at which families can socialize, dance to local bands’ music, and learn more about the realities of farming in the local ecosystem.